July gave us record amounts of rain. So, how about a little snow for August? That's part of what

Carrie Haddad Gallery offers in its annual

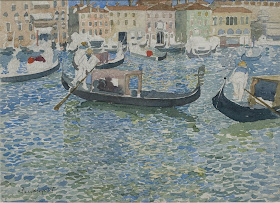

Landscapes exhibition, which opens with a reception tonight (Saturday) from 6 to 8 p.m. The snow is courtesy of Washington County painter Harry Orlyk (image above); the other featured artists are Tracy Helgeson, Robert Koffler, and Don Bracken.

While it might seem underwhelming conceptually, this summer landscape show sets a very high standard and even gets pretty edgy with Bracken's work, where extreme texture and a narrow tonal range evoke Anselm Kiefer. Koffler's neo-Modernist woodsy scenes range from seductively vivid to pensive (in his less colorful moments). Helgeson's more eye-pleasing palette and geometry dominate the big front room, where a surprisingly diverse collection of her quasi-formulaic works are grouped in exuberant clusters. And Orlyk, painting feverishly in his well-established Impressionist style, is brilliant as always.

Additional spotlight exhibitions by Linda Cross, Thomas Locker, and Russell DeYoung in the gallery's back room and upstairs spaces extend the landscape theme and, apart from Locker's cloying Luminism, maintain the level set by the feature show's artists.

Down at the opposite end of Warren Street,

BCB Art has a solo show of works on paper by Sasha

Chermayeff (shown below in her studio) that ends Aug. 9. Chermayeff's father is the graphic designer Ivan Chermayeff, and the graphic influence is readily apparent in this direct, gestural work that emphasizes primary colors and pared-down technique.

There is a childlike quality to this work that may or may not appeal to serious art viewers. I found it somewhat decorative, reading a bit more as designs for textiles than as resolved paintings - but a few of the works do go beyond the surface.

A collection of folded paper accordion books added heft to the presentation; also, a group of six smaller paintings, framed and presented in a grid, worked quite well.

A counterpoint to Chermayeff's no-frills approach comes in the form of the layered and very thoughtful mixed-media work of Yale Epstein, now on view at Albert Shahinian Fine Art. The solo exhibition, titled Inscriptions II: The Eloquent Brush, opened in late June and has been extended to Sept. 13.

Epstein, based in Woodstock, is in his 70s and has a very long list of achievements, including many shows locally and internationally, dozens of public and corporate collections, and a rapidly growing list of commissions. Known primarily as a printmaker, he moves easily from press, ink, and paper to oil, acrylic, and canvas. A strong, coherent selection of all his mediums is presented in this beautiful, multi-room gallery.

Among the more impressive pieces in the show is Chronicle I, a 4-foot painting reproduced at left. Its colors, composition, and calligraphy are representative of much of the work in the show, all of which has a distinct Oriental flavor. I was told that Epstein's characters are invented but, to one not schooled in Chinese writing, they felt authentic; it's interesting to note that a number of his commissions have been for sites in the Far East.

Among the more impressive pieces in the show is Chronicle I, a 4-foot painting reproduced at left. Its colors, composition, and calligraphy are representative of much of the work in the show, all of which has a distinct Oriental flavor. I was told that Epstein's characters are invented but, to one not schooled in Chinese writing, they felt authentic; it's interesting to note that a number of his commissions have been for sites in the Far East.

What Epstein aims for - and achieves - in this work is an experience of cross-cultural communication that transcends both time and geography, as alluded to in his introduction to a beautifully printed color catalog that accompanies the show. It is an extremely rich body of work by an artist totally immersed in the essence of history and connection.

A quite different, but equally compelling solo show of

paintings is offered at

John Davis Gallery through Aug 16. David Hornung combines heavily pigmented oils with encaustic to produce flat colors that are aesthetically similar to gouache, a medium he also favors. Plenty of works in both mediums are featured in this very clean presentation, where Hornung shares cheerful, allegorical scenarios that verge on illustration but remain poignantly personal (the example above is titled

Remembering M).

It might be hard to pull this off if Hornung were less of a painter, but the work is no less convincing for being rather charming. I always find an encounter with paintings of such skill to be the perfect antidote to our era's emphasis on concept over craft. This work shows you can be original without abandoning strong technique.

And, speaking of original, there's a brilliant installation in the Davis Gallery's carriage house (out back, beyond the sculpture garden) by Leticia Ortega and Dionisio Cortes that conjures a stunning and relevant experience out of the simplest of materials: plastic bags of water. Titled when skies are hanged, it has been extended to Aug. 16, and is a must-see.

My final stop of the day was at Carrie Haddad Photographs, where a show titled Afterglow: Four Photographers and the Hand-Held Light will run through Aug. 30. Comprising photographic images that have been created through the use of hand-applied lighting with long exposures, this exhibition brings back an alternative technique, often called "painting with light" that was popular in the '70s.

My final stop of the day was at Carrie Haddad Photographs, where a show titled Afterglow: Four Photographers and the Hand-Held Light will run through Aug. 30. Comprising photographic images that have been created through the use of hand-applied lighting with long exposures, this exhibition brings back an alternative technique, often called "painting with light" that was popular in the '70s.

In fact, some of the work in the show by David Lebe dates just about that far back, which is fine with me. (Side note: not all "contemporary" art needs to have been made last week to be worth looking at.) Along with Lebe, Robert Flynt and Warren Neidich work in black and white; Gary Schneider is the lone color practitioner in the group.

All four work directly with the human form (Lebe's Scribble, shown above, notwithstanding), in significantly varied ways. Neidich presents a grim grid of 12 images against a black background that emphasizes the skull-like qualities of the human head. Lebe works mostly with the male nude, sometimes adding hand-colored elements, to evoke a spiritual sexuality. Flynt crosses boundaries and genres by montaging and collaging elements into a wall-sized constellation of images pinned, flush-mounted, clipped in glass, or framed.

All of these are strong - but my favorite is Schneider, whose full-length, life-size frontal nudes (the one shown at right is titled Laura) evoke cadavers, despite the subjects' open eyes and alert expressions. They also afford the rare opportunity to examine a living stranger's anatomy, nasty bits included, which I'm pretty sure all of us can't resist doing any more than a dog can resist its rude sniffings.

All of these are strong - but my favorite is Schneider, whose full-length, life-size frontal nudes (the one shown at right is titled Laura) evoke cadavers, despite the subjects' open eyes and alert expressions. They also afford the rare opportunity to examine a living stranger's anatomy, nasty bits included, which I'm pretty sure all of us can't resist doing any more than a dog can resist its rude sniffings.

So much comes down to sex and death; Schneider's work, and this show as a whole, makes that quite clear, but in a way that still feels life-affirming. And that's what good art is all about.

NOTE: Hudson's galleries have varied hours; most are open at least from noon to 5, Thursday through Monday, but to be sure, check their websites.

The Hudson River has been a wellspring of artistic inspiration for centuries, and for one very good reason: the light. Anthony Thompson paints that light, and the river, with exceeding skill and concentration, as evidenced by his semi-retrospective solo show, which runs through Sept. 8 at Martinez Gallery in Troy. Though the gallery has limited hours (see below), tonight's Troy Night Out affords a long evening's opportunity to go have a look.

The Hudson River has been a wellspring of artistic inspiration for centuries, and for one very good reason: the light. Anthony Thompson paints that light, and the river, with exceeding skill and concentration, as evidenced by his semi-retrospective solo show, which runs through Sept. 8 at Martinez Gallery in Troy. Though the gallery has limited hours (see below), tonight's Troy Night Out affords a long evening's opportunity to go have a look. because it is a fully realized painting) and larger final version of Olana Sunburst (shown at right). This is a rather disquieting image, as tempestuous as a Turner, which seems representative of the dual nature of human spirituality.

because it is a fully realized painting) and larger final version of Olana Sunburst (shown at right). This is a rather disquieting image, as tempestuous as a Turner, which seems representative of the dual nature of human spirituality. Martinez Gallery's hours are Thursday-Sunday, 2:00 to 4:30 p.m., and by appointment. It would be nice if they were more expansive, but the fact that this commercial gallery has survived in the Capital Region since 2001, which is something of a record, shows they are doing many things right. Go see for yourself what it's about.

Martinez Gallery's hours are Thursday-Sunday, 2:00 to 4:30 p.m., and by appointment. It would be nice if they were more expansive, but the fact that this commercial gallery has survived in the Capital Region since 2001, which is something of a record, shows they are doing many things right. Go see for yourself what it's about. And, while you're at it, check out another Hudson River show that opens tonight (Friday, Aug. 28) and runs through Sept. 23 at Clement Art Gallery, which is just a few steps from Martinez. The show, titled Down by the River, presents a large body of black-and-white photographs by John Whipple that are part of a long-term project looking at many aspects of the river and its inhabitants. I recommend it.

And, while you're at it, check out another Hudson River show that opens tonight (Friday, Aug. 28) and runs through Sept. 23 at Clement Art Gallery, which is just a few steps from Martinez. The show, titled Down by the River, presents a large body of black-and-white photographs by John Whipple that are part of a long-term project looking at many aspects of the river and its inhabitants. I recommend it.