The Pop and the political intermingle like two skeins of colored yarn in Critical Stitch, which opened in October and runs through Dec. 19 at Union College’s Mandeville Gallery. Curated by Lorraine Morales Cox, a Union professor of contemporary art and theory, the exhibition features fiber-based work by 12 artists from all over: Maine, Michigan, Newfoundland, Texas, Ohio, and Rhode Island all have representatives, while California and New York City have a few each in the show.

The Pop and the political intermingle like two skeins of colored yarn in Critical Stitch, which opened in October and runs through Dec. 19 at Union College’s Mandeville Gallery. Curated by Lorraine Morales Cox, a Union professor of contemporary art and theory, the exhibition features fiber-based work by 12 artists from all over: Maine, Michigan, Newfoundland, Texas, Ohio, and Rhode Island all have representatives, while California and New York City have a few each in the show.Considering that it was organized by someone whose “primary areas of research include feminist and postcolonial theory, critical race studies, and transcultural identity,”

Critical Stitch actually offers a pretty enjoyable experience, with a sense of humor running through much of the content-charged art. The fact that it includes four men among the knitters and embroiderers adds to the intrigue of exploring its many facets and undercurrents.

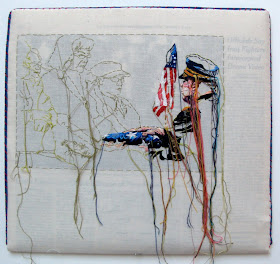

Critical Stitch actually offers a pretty enjoyable experience, with a sense of humor running through much of the content-charged art. The fact that it includes four men among the knitters and embroiderers adds to the intrigue of exploring its many facets and undercurrents.Morales Cox has presented quality work in every case, even if some of the ideas are a bit overwrought or unoriginal. The skill employed by the artists ranges from appropriately adequate to outright impressive. For example, Lauren DiCioccio’s meticulously embroidered renderings of consumer detritus, such as the ubiquitous plastic bag with a happy face on it, and layered newspaper clips (one is shown above at right) show the potential of colored thread as a medium that transcends traditional crafts.

Two other artists, Margarita Cabrera and Alicia Ross, also make significant use of thread itself as a medium, but in different ways. Cabrera sews Oldenburgish facsimiles of small appliances out of leatherette (one is shown at left), leaving lots of loose threads to represent the hand work of the manufacturing process she is channeling from her Mexican roots. Ross, using computerized cross-stitchery, represents female objects of desire transformed from their commercial sources in pornography into oddly appealing yet repellent images (one is shown at the top of this post).

Two other artists, Margarita Cabrera and Alicia Ross, also make significant use of thread itself as a medium, but in different ways. Cabrera sews Oldenburgish facsimiles of small appliances out of leatherette (one is shown at left), leaving lots of loose threads to represent the hand work of the manufacturing process she is channeling from her Mexican roots. Ross, using computerized cross-stitchery, represents female objects of desire transformed from their commercial sources in pornography into oddly appealing yet repellent images (one is shown at the top of this post).Among the men are two whose thicker threads in hooked rugs and needlepoint pillows present ironically softened visions of cultural touchpoints – Richard Bassett’s throw pillows fetishize the Kennedy assassination, while Rob Conger enters the realm of kitsch with his acrylic wall hangings taken from Disney and other corporate source material.

I found Johanna Unzueta’s installation of soft felt to be the wittiest piece in the show (and, not surprisingly, the least political). Color-coded to match the Mandeville’s décor, her faked utility pipes could evoke issues of stealth and terrorism and subversion, but are also just a fun thing to come upon. Also darkly humorous is Dave Cole’s woven and stitched bulletproof Kevlar Onesie, a chilling suggestion if there ever was one (shown above at right).

I found Johanna Unzueta’s installation of soft felt to be the wittiest piece in the show (and, not surprisingly, the least political). Color-coded to match the Mandeville’s décor, her faked utility pipes could evoke issues of stealth and terrorism and subversion, but are also just a fun thing to come upon. Also darkly humorous is Dave Cole’s woven and stitched bulletproof Kevlar Onesie, a chilling suggestion if there ever was one (shown above at right).Some of the work in the show pushes a little further into traditional gender roles, such as Mark Newport’s goofy, oversized, knitted superhero outfits and Laurel Roth’s obscenity-laden PMS Quilt, featuring crocheted-together panty liners. More touching and elegant is Roth’s animal-based work, such as her Carolina Parakeet (actually a carved pigeon wearing the colors of the extinct bird, it is represented below at right).

Other work does little to inspire or break new ground. Barb Hunt has re-created a variety of land mines in yarn – something done far more effectively years ago by Conrad Atkinson using glass and porcelain; Vadis Turner bores by stitching the names of such role models as Britney Spears and Paris Hilton onto an antique quilt; and Tamara Kostianovsky’s mute presentation of fabric and fiberfill sides of beef (shown at the bottom of this post) seems to go nowhere, despite elaborate textual efforts to infer otherwise in the catalog accompanying the show.

Other work does little to inspire or break new ground. Barb Hunt has re-created a variety of land mines in yarn – something done far more effectively years ago by Conrad Atkinson using glass and porcelain; Vadis Turner bores by stitching the names of such role models as Britney Spears and Paris Hilton onto an antique quilt; and Tamara Kostianovsky’s mute presentation of fabric and fiberfill sides of beef (shown at the bottom of this post) seems to go nowhere, despite elaborate textual efforts to infer otherwise in the catalog accompanying the show.Overall, Critical Stitch is a nicely produced, thoughtfully curated show of worthwhile but somewhat disappointingly clever conceptual art. I think it shows just how much academic theory has affected the contemporary artistic landscape. Even when dealing with extremely emotionally charged subject matter, these artists seem to have traded the raw feelings, passion, and intensity of a bygone age for muted, funded, and packaged products that aim mainly to please the elite who own galleries, confer MFAs, and write for art magazines. It would be self-flattery to believe in the power of such work to cause any real change, despite its political and cultural messages.

Rating: Recommended

No comments:

Post a Comment