A year ago at this time, I summed up the first complete year of Get Visual with philosophical musings, memorable highlights, and encouragement to all of you to support the arts any way you could in these tough times. Well, it seems not very much has changed – Get Visual has completed another calendar year of reviews from our incredibly rich region’s offerings, and the arts are still taking heavy blows from the ongoing (though supposedly easing) recession.

Among the lowlights: NYSTI crashed and burned, swept away by multiple fiscal malfeasances; the city of Albany cut its entire $350,000 annual arts budget (to which the Common Council had the good sense to restore a fractional $65,000, targeting “small arts groups,” according to the Times Union); Proctors bought and sold a couple of buildings, forcing the move of the “working” artists’ studio to off-street quarters; and the number of art shows overall dropped significantly, as cash-strapped presenting organizations sought ways to cut costs (extending a show for a few months is a quick way to do that).

Despite the downs, there were at least 50 shows out there that Get Visual reviewed, and the traffic here has increased by just about 50%, jumping from 15,000 visits tallied in the first year to 22,000 in the second (for a current total of 37,000). And, while there may have been fewer exhibitions to track – though that did not save us from missing a whole lot of them, naturally – the quality of those exhibitions remained astonishing.

Though I was planning to break tradition and do a Top Ten list this time, the 17 shows on my “short” list will not whittle down that easily. Even so, as I said, important shows were missed, and while that’s almost unforgivable, please allow me to apologize foremost for failing to make it to MASS MoCA during 2010 (soon to be rectified!), and in general for any other worthwhile efforts that I didn’t catch. I welcome, and would greatly appreciate, any comments from readers that mention such worthy, overlooked endeavors.

So, with a little bit of category manipulation (but no further ado), here are the Capital Region’s best shows of 2010, each linked to its original review as it appeared on Get Visual):

Category One - Major Museums: As usual, there were summer blockbusters, and the one that stood out above all others was Picasso Looks at Degas at the Clark Art Institute (image at left). We were extremely lucky to have this international event make its only North American stop in our backyard, and it absolutely lived up to the hype – unless, for some reason, you hate great paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints. Also worthy of supreme status was Andrew Wyeth: An American Legend at The Hyde Collection, which should have been sufficient to convert any remaining doubters that Wyeth truly matters as a 20th-century artist; and Not Just Another Pretty Place: The Landscape of New York at the New York State Museum, which earned my first Must See rating (the system was only recently instituted) for the way it showcases the surprising depth, breadth, and quality of the NYSM’s permanent collection (and it’s still on view through March 3, hint, hint). Also mentionable in this category is the Norman Rockwell Museum’s excellent exposure of Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera.

Category One - Major Museums: As usual, there were summer blockbusters, and the one that stood out above all others was Picasso Looks at Degas at the Clark Art Institute (image at left). We were extremely lucky to have this international event make its only North American stop in our backyard, and it absolutely lived up to the hype – unless, for some reason, you hate great paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints. Also worthy of supreme status was Andrew Wyeth: An American Legend at The Hyde Collection, which should have been sufficient to convert any remaining doubters that Wyeth truly matters as a 20th-century artist; and Not Just Another Pretty Place: The Landscape of New York at the New York State Museum, which earned my first Must See rating (the system was only recently instituted) for the way it showcases the surprising depth, breadth, and quality of the NYSM’s permanent collection (and it’s still on view through March 3, hint, hint). Also mentionable in this category is the Norman Rockwell Museum’s excellent exposure of Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera. Category Two - Solo Exhibitions (large): A very crowded category, probably because I generally prefer the in-depth coverage of a solo to the smatterings of group shows – but maybe also because there just happened to be a bunch of great solos this year, and a bunch of those were pretty substantial. Top of the list, because it was as challenging as it was rare, is Larry Poons: Recent Paintings at the Esther Massry Gallery. Also very impressive: Jules Olitski: An Inside View at Opalka Gallery (image above at right); Edward Avedisian: Retrospective at Carrie Haddad Gallery; Carroll Dunham Prints: A Survey at the University Art Museum; and Fred Tomaselli at the Tang Teaching Museum. All were comprehensive surveys of important, innovative bodies of work that the curators and presenting organizations pulled off flawlessly. It’s worth noting that two of these shows were of prints (Dunham and Olitski) and one was of mixed media (Tomaselli) – it’s not always about painting.

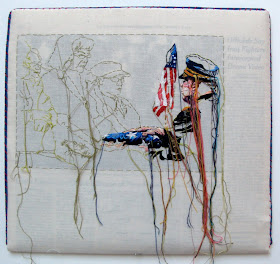

Category Two - Solo Exhibitions (large): A very crowded category, probably because I generally prefer the in-depth coverage of a solo to the smatterings of group shows – but maybe also because there just happened to be a bunch of great solos this year, and a bunch of those were pretty substantial. Top of the list, because it was as challenging as it was rare, is Larry Poons: Recent Paintings at the Esther Massry Gallery. Also very impressive: Jules Olitski: An Inside View at Opalka Gallery (image above at right); Edward Avedisian: Retrospective at Carrie Haddad Gallery; Carroll Dunham Prints: A Survey at the University Art Museum; and Fred Tomaselli at the Tang Teaching Museum. All were comprehensive surveys of important, innovative bodies of work that the curators and presenting organizations pulled off flawlessly. It’s worth noting that two of these shows were of prints (Dunham and Olitski) and one was of mixed media (Tomaselli) – it’s not always about painting. Category Three - Solo Exhibitions (small): Again, many good choices here. The top spot has to go to Michael Millspaugh (once again, not a painter), whose exuberant, exhaustive installation at Lake George Arts Project set him apart from the everyday artists of this - or any - region (image above at left). Also worthy of year-end praise: Claude Carone: Paintings at John Davis Gallery; and Monica Miller: Diary of a Trespasser at Joyce Goldstein Gallery. Boxed Sets, a retrospective of dioramas and stage designs by Charles Steckler at the Perrella Gallery at Fulton-Montgomery Community College gets honorary mention here because, even though I didn’t actually see it, other similar recent shows by Steckler were unalloyed knockouts - I'm certain this must have been, too.

Category Three - Solo Exhibitions (small): Again, many good choices here. The top spot has to go to Michael Millspaugh (once again, not a painter), whose exuberant, exhaustive installation at Lake George Arts Project set him apart from the everyday artists of this - or any - region (image above at left). Also worthy of year-end praise: Claude Carone: Paintings at John Davis Gallery; and Monica Miller: Diary of a Trespasser at Joyce Goldstein Gallery. Boxed Sets, a retrospective of dioramas and stage designs by Charles Steckler at the Perrella Gallery at Fulton-Montgomery Community College gets honorary mention here because, even though I didn’t actually see it, other similar recent shows by Steckler were unalloyed knockouts - I'm certain this must have been, too. Category Four - Group Exhibitions: Reflections on Water in American Painting at the Arkell Museum (image at right) was a revelation, because traveling shows from private collections usually come off as self-serving and are rarely as great as the presenters would like to think. But not this one! Another group show that transcended the category by the sheer quality of juror Ian Berry’s selections was this year’s Fence Select at the Arts Center of the Capital Region. Also at the ACCR, Battlesight: Dispatches from Iraq and Afghanistan by International Photographers stood out as a hard-hitting, carefully planned combination of three photojournalists’ personal visions of war (oddly enough, it’s the only show of photographs that made this list). Then and Now at Albany Center Gallery effectively combined the seemingly unrelated talents of fiber sculptor Mimi Czajka Graminski, painter Iona Park, and photographer Jeri Eisenberg. And, finally, Here and There: Two Degrees of Separation, a show of 20 printmakers at the Union College Arts Atrium, again broke the mold by pulling together a very diverse collection and, somehow, pulling it off.

Category Four - Group Exhibitions: Reflections on Water in American Painting at the Arkell Museum (image at right) was a revelation, because traveling shows from private collections usually come off as self-serving and are rarely as great as the presenters would like to think. But not this one! Another group show that transcended the category by the sheer quality of juror Ian Berry’s selections was this year’s Fence Select at the Arts Center of the Capital Region. Also at the ACCR, Battlesight: Dispatches from Iraq and Afghanistan by International Photographers stood out as a hard-hitting, carefully planned combination of three photojournalists’ personal visions of war (oddly enough, it’s the only show of photographs that made this list). Then and Now at Albany Center Gallery effectively combined the seemingly unrelated talents of fiber sculptor Mimi Czajka Graminski, painter Iona Park, and photographer Jeri Eisenberg. And, finally, Here and There: Two Degrees of Separation, a show of 20 printmakers at the Union College Arts Atrium, again broke the mold by pulling together a very diverse collection and, somehow, pulling it off.Notably absent here is The Jewel Thief, currently on view at the Tang; I predict it would have been on this list had I seen it yet. Please watch this space for a review of The Jewel Thief that will run soon. And have a fantastic year of art viewing in 2011.

During my annual pilgrimage to the Lake George Jazz Weekend last week I had the opportunity to look in on Julie Anne Mann's Intrinsic Nature exhibition at

During my annual pilgrimage to the Lake George Jazz Weekend last week I had the opportunity to look in on Julie Anne Mann's Intrinsic Nature exhibition at

.jpg)

.jpg)